Careers in Clinical Animal Behaviour

What is a clinical animal behaviourist?

A clinical animal behaviourist works with animals and their caregivers (whether owners, rescue centres or even zoos) to resolve behaviour problems and disorders. These behaviour problems are often serious and may for instance involve biting, excessive barking, inappropriate toileting, or repetitive obsessive behaviours. Different behaviourists often specialise in working with particular species, such as horses, dogs or cats. Behaviourists may work full or part-time. Largely they are self-employed, but some are employed for example by animal welfare charities, or as part of a veterinary practice.

The role of a clinical animal behaviourist is interconnected with, but different to animal training instructors, who may for instance run group classes, or to animal behaviour technicians, who usually provide more preventative advice to stop behaviour problems from developing in the first place. You can read more about these different roles on the Animal Behaviour and Training Council (ABTC) web site. The ABTC is an umbrella organisation made up of several practitioner and advisory organisations, which is aiming to regulate the animal behaviour and training industry.

A clinical animal behaviourist works one-on-one with an animal and their caregiver, often in their home environment, or in a clinic. They take a detailed case history and diagnose the reasons behind a behaviour problem. This leads to a behaviour treatment plan, which the clinician then helps the animal and their caregivers work through over a period of time, which can range from a few weeks to several months.

Behaviour consultations often involve working to change an animal’s emotional state, such as fear or anxiety. There may also be a medical reason for a behaviour problem, and this is one of the many reasons why the behaviourist should only work upon referral from the animal’s vet and keep them involved throughout the behaviour consultation process. There are also vets who specialise in behavioural medicine. They are able to provide greater insight into how the physical health of the animal could be interconnected with their behaviours and underlying emotions. Veterinary behaviourists are also able to advise what possible medical tests may need to be carried out prior to a behaviour consultation, or if some type of medication could form part of a behaviour treatment plan.

How do I become a clinical animal behaviourist?

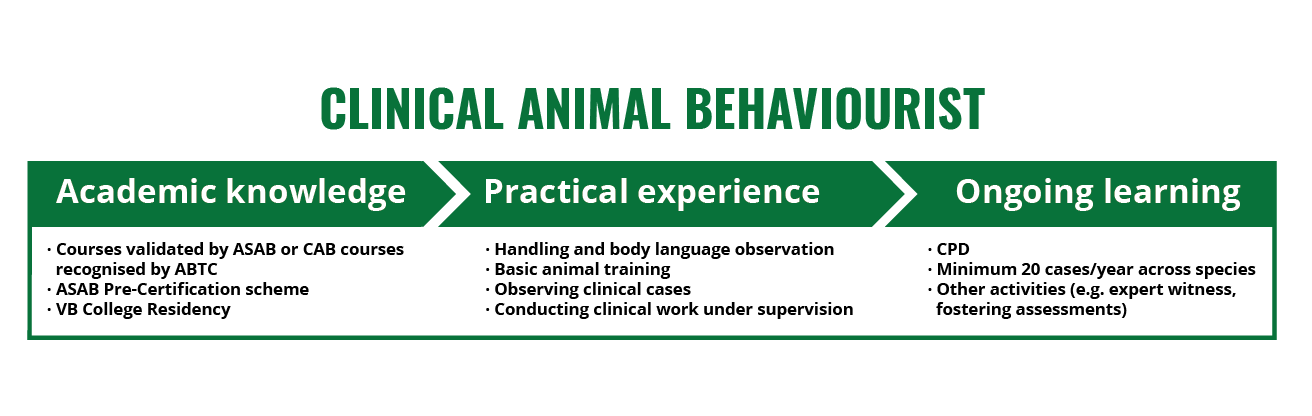

There are lots of different routes available for becoming a clinical animal behaviourist –practitioners have come to the job through many different paths. Essentially though there are two sides to the job that you need to develop in order to practise as a clinical animal behaviourist: academic knowledge and practical experience.

FAB Clinicians believes that the accrediting body that decides whether you have the appropriate knowledge, skills and standards of best practice should be external to professional associations and course providers. Currently in the UK the only independent accreditation route for clinical animal behaviourists (for both vets and non-vets) is the Certificated Clinical Animal Behaviourist (CCAB) route run by CCAB Certification Ltd

Veterinary Behaviourists may also choose to seek further training to specialise in behavioural medicine through a residency. In UK and Europe, this would involve eventually becoming a Diplomate (DipECAWBM(BM)) of the European College of Animal Welfare and Behavioural Medicine. In North America, it would involve working towards becoming a Diplomate (DAVCB) of the American College of Veterinary Behaviourists. In Australasia, it would involve becoming a Member and Resident of the ANZCVS Veterinary Behaviour Chapter, then working towards becoming a Fellow (FANZCVS).

a) Academic knowledge

When looking for useful courses that will help contribute towards your knowledge about clinical animal behaviour, look for higher education courses provided by accredited institutions. In the UK these would be UK Government Qualification FHEQ courses at Levels 4, 5 and 6. Knowledge of the following subject areas are important for starting a career in clinical animal behaviour:

- Principles of ethology;

- Animal welfare science;

- Theories of animal learning and emotions;

- Functional anatomy and physiology of the vertebrate nervous system and endocrine systems;

- Clinical principles, procedures and practice;

- Animal law and ethics;

- Interaction between health and behaviour in vertebrate animals;

- Research skills.

We recommend looking at the list of courses validated by CCAB certification Ltd. and the clinical animal behaviourist courses recognised by ABTC. Some are provided either full-time or part-time, while others are offered on a distance-learning basis.

If you already have some relevant academic background, then CCAB Certification Ltd also has a system called ‘pre-certification’ for working out what the possible gaps in your knowledge might be. Some subject areas only require coverage at Level 4 (or even just by attending a CPD event), others require learning up to Level 5 and to Level 6. There are some education institutions that offer one-off modules for individuals who require just a few gaps to be filled, rather than needing to enrol in entire degrees or diplomas encompassing several modules. We recommend choosing courses run by research-active institutions, or with content informed by some of the latest scientific studies in the field. Note though that it may be cheaper, quicker and/or easier in the long run if you enrol in one of the complete validated or recognised courses linked above.

If you join us as a Student Member, FABC will support you through this process. We welcome applications from anyone who as a minimum is enrolled in a Level 5 course with at least one animal or psychology related module.

b) Practical experience

People come to this job through a variety of different paths. Nonetheless, normally once you understand all the theory behind clinical animal behaviour, you can then start to gain the practical skills and experience needed to become a practitioner. The first step is to become proficient in the handling and basic training of animals. You need to be able to adeptly observe body language, interact with and train your chosen species in various basic tasks. In other words, you need to be competent in practically approaching several different individual animals across a range of temperaments in a basic training task, such as clicker training an unfamiliar dog to sit. For example, this essential hands-on experience could be gained by working at a cattery, vets, stables or rescue kennels.

From this strong practical foundation, you can then begin to build on your clinical training. This can be done by a variety of means, such as through clinical training provided by an employer or a charity sector organisation, or gradually through consultations that you run in your own business, or by shadowing and working with well-established clinicians. If you do practise independently, it is very important for the welfare of the animal you are working with, as well as the owners, other animals and people it could come into contact with, that you know the limits of your own competence and do not practise outside them. Otherwise there may well be serious legal ramifications for you in the future.

FABC provides a mentoring scheme for Candidate Members, which will support you through your clinical training. This scheme is not a requirement for membership, or for becoming accredited as a clinical animal behaviourist, but it can be a helpful addition to guide you through your journey.

To develop your understanding of what happens at a behaviour consultation it is helpful to observe consultations run by a number of established clinical animal behaviourists (and veterinary behaviourists) in your chosen species. Everyone is different, but as a guideline you could aim to observe about 10 cases across a range of different behaviour problems. Once you and your supervising clinicians (mentors) feel confident in your abilities, then you can start gradually taking more of a lead in certain cases. It’s a good idea to be mentored through at least 10 cases where you have taken the lead, dealing with various issues. Some people find it helpful to be mentored through many more cases.

When you feel that you have enough clinical experience in leading your own cases (perhaps about 35 cases or more), then you can apply to be independently accredited. For instance, if you would like to be a canine behaviourist, then you should have plenty of experience in treating the following kinds of behaviour problems:

- Aggression towards people or dogs (strangers or familiar);

- Problems related to someone’s absence;

- Apparent fearful or phobic behaviour;

- Problems related to training, over-excitement or attention-seeking;

- Apparent predatory behaviour;

- Inappropriate toileting;

- Repetitive behaviours e.g. tail chasing.

What do you do when you have become an independently accredited clinical animal behaviourist?

Learning on the job will never stop throughout your career as a clinical animal behaviourist! You should keep up-to-date with the latest techniques, ideas and research being conducted across the sector through CPD. You will find that you’ll frequently be adapting and applying your newly acquired knowledge to your clinical practice. You should aim to maintain a minimum caseload (approximately 20 a year) to keep your skills ticking over.

There are many other types of activities that a clinical animal behaviourist may become involved in, such as expert witness work, animal assessments for fostering or school placements, media consultation, policy development, education and research. The diversity of the job, including the people and the animals we meet is what makes it such a rich, fascinating profession to be a part of!

What Drives Us

Our Mission

To promote evidence based behavioural support for animals and their carers, to the highest scientific standards, in an empathetic and compassionate manner.

To forge strong links between animal carers, behaviourists and veterinary professionals.

To support the development of independently accredited practitioners in the field of clinical animal behaviour through mentoring, continuing professional development and supportive fellowship.